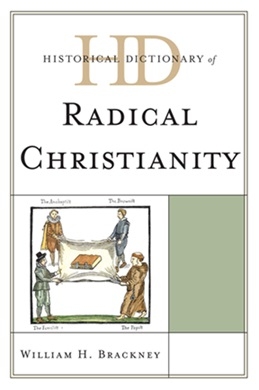

Brackney - Historical Dictionary of Radical Christianity - модуль BibleQuote

William H. Brackney - Historical Dictionary of Radical Christianity

Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2012. – 380 p.

ISBN-13: 978-0810871793

ISBN 978-0-8108-7179-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8108-7365-0 (ebook)

William H. Brackney is the Millard R. Cherry Distinguished Professor of Christian Thought and Ethics at Acadia Divinity College and a member of the faculty of theology of Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada. He has been chair of the Department of Religion and professor of religion at Baylor University; dean of theology and professor of historical theology at McMaster University; vice president and dean and professor of the history of Christianity at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary; and associate professor of historiography at Colgate Rochester Divinity School, where he also was curator of the Samuel Colgate Baptist Historical Library and executive director of the American Baptist Historical Society. The author of more than 30 books and scores of articles, Brackney holds degrees from the University of Maryland, Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Temple University, where his Ph.D. was conferred with distinction. He teaches in the areas of historical theology and ethics and directs the Acadia Centre for Baptist and Anabaptist Studies. For a number of years, Brackney has taught graduate seminars in Dissenter and radical Christianity, and he is currently engaged in a research project, Bibliotheca Dissidentium, for which he is preparing a volume on the 17th century. Brackney’s recent published works include Studying Christianity: The Critical Issues (2010); Congregation and Campus: North American Baptists in Higher Education (2009); Historical Dictionary of the Baptists (2nd edition, 2009); Baptists in North America: A Historical Perspective (2006); A Genetic History of Baptist Thought (2005); and Human Rights and the Christian Tradition, which is part of the series that he also edited, Human Rights and the World’s Great Religions (5 volumes, 2004).

* * *

Seeking the roots of any movement, especially one as long and broad as Christianity, is not an easy task, yet it has been undertaken time and again. The reasons for this exploration are compelling, since some feel that the religion has gone off in the wrong direction and that the trajectory can only be corrected by returning to those roots, the radici. Indeed, can is too mild a term, and must is the one that occurs to most radicals. Thus, the history of radical Christianity is almost as long as that of Christianity itself, and it will likely continue as long as the mother religion. Admittedly, not all of the attempts to redirect the religion were successful, at least not in the eyes of the “authorities,” clerical, state, or indeed academic, but they were all good-faith efforts, and some have moved the church in different and sometimes even better directions, while others were rejected, forcefully crushed, or died out on their own. Thus, the history of radical Christianity is littered with sects, schisms, and heresies, but now and then there also emerge new variants of Christianity, which have held up over time and are now accepted as part and parcel of the overall religion.

Historical Dictionary of Radical Christianity traces these attempts for a change in course, the failures as well as the successes, and gives us a feeling for the incredible breadth and vitality of Christianity, for without them it might not have moved or, more accurately, it might just have kept on moving in whatever direction it happened to be going at the time without warning that perhaps the trajectory should be corrected. The problematic nature of radicalism in this context is clearly revealed in the introduction, which shows how that concept, too, has evolved for more than 20 centuries. The introduction also provides a typology of the radical groups and their leaders. This typology is useful in the dictionary section, which contains entries on hundreds of different groups and shows how they were created and developed and, in some cases, how and why they disappeared, or, for the select few, how they are presently faring and, in some cases, prospering. Most of the entries are on specific groups, and some are on specific leaders, but there are also key entries that reflect on the basic concepts that help bring order out of a seemingly chaotic situation. Naturally, no matter how complete this book may be, and it does cover an impressive number of groups, there are some that are missing, and there is certainly more to be said about those that do appear, thus the bibliography is a good starting point for further study.

This book was written by William H. Brackney, who is the Millard R. Cherry Distinguished Professor of Christian Thought and Ethics and director of the Acadia Centre for Baptist and Anabaptist Studies at Acadia University and Divinity College in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada. Prior to this, Brackney taught at Baylor University, McMaster University, and Colgate Rochester Divinity School. Most of the material in this work arises out of research and a course he taught for several years at Baylor. During his long career as an academic, in addition to lecturing on radical Christianity, Brackney has written extensively on the subject, including articles for historical and biographical journals and handbooks and a book entitled Studying Christianity (2010). He has also written on other topics largely connected with Baptists and the Free Church tradition, including two editions of the Historical Dictionary of the Baptists (1999, 2009) in this same series. This latest effort certainly takes him further afield and covers an extraordinary range of groups, some of which have, alas, been long forgotten, while others remain topical, but all of which provide their own lessons.

* * *

Historical Dictionary of Radical Christianity addresses and exhibits the Christian tradition in its broadest expressions. I am not only concerned about historic “mainstream” Christianity that may be defined by core values or a kerygma, or by reference to a creed or confessional document, but also the numerous rivulets that have defined a much wider religious tradition during the 20 centuries of Christian thought and life. In this coverage, one will find predictable offspring that are clearly within most definitions of reasonable orthodox Christianity, as well as numerous groups that have heretofore fallen away from any classification of “Christian.” I have “restored” them to the discussion.

A new paradigm is in order. For approximately 18 centuries, mainstream Christian groups have been assessing beliefs and behaviors according to the maintenance of their own positions or institutions. The result has been to establish “orthodoxy” for the teaching, rites, and functions of the faith. Those people, movements, and traditions that fall outside the consensus are labeled (sometimes violently) “heresy,” and steps are taken to silence and eradicate them, and even to destroy the documents and literature defining them. Sabellianism and Pelagianism are classic examples. An entire discipline and literary genre has grown up around “heresiology.” It is not my intention to reverse those decisions with the stroke of a key, or to suggest that any teaching that denies fundamental values of Christianity is (or should be) somehow now acceptable.

Rather, I argue that the Christian faith and life now constitutes a self-critical religious tradition two millennia old and virtually global in cultural variations, and it has produced experiments and permutations that have roots in the original essence and values of Jesus of Nazareth and the first century leaders and churches, usually referred to as the “Apostolic Tradition.” Contexts and creativity produce change and variety, and the variety is in turn evaluated against the original and core ideas.

Some of the variety has often been labeled “radical.” At first glance, this may be taken to mean “extreme,” “abrupt,” or “dramatic,” in contrast with the gradual or progressive (in stages) evolution of ideas.1 Illustrative of this definition of “radical” as synonymous with change agency is Michael Barkun, who describes radicals as having a mandate for change, relying upon organizational skills, characterized by hard work, enduring loyalties, an understanding of means-ends relationships and understanding the instrumentality of social organizations.2 Several groups included here fit that definition. Even more correctly to the original idea content of the term (radix/radici = a root), by radical I mean an identifiable person/group that sought in some way to restore or recover the original essence of Christianity, as witnessed in the New Testament scriptures and literature of first-century Christianity.

* * *

CONCOREZZANS

(T)

A sect of Cathars that differed, in particular, from the Albanensians on the dualistic principle of God. Concorezzan adherents were concentrated throughout Lombardy, and, in the mid-12th century, numbered about 500. In contrast with Albanensians, Concorezzans held to a more unified doctrine of God, who had a creature named Lucifer to order the visible world from the material that God had originally created: earth, air, fire, and water. Christ was also God’s creature, whom God sent to rescue those whom God wished to save. They believed sin was derived from the freedom of the will and was illustrated in what happened to both humans and angels. Concorezzans held that souls were reproduced through sexual intercourse, and that in the consummation, bodies would dissolve into matter, with souls being liberated. Salvation depended upon the free choice of humans, saved through the act of the consolamentum. A greater number of people would be damned than saved in Cathar economy.

Two categories of Concorezzans were identified. One group, supposedly the ancient of the two, followed Nazarius, bishop of Concorezzo (c. 1190–1240). Nazarius taught that Mary was an angel and only an apparent mother of Jesus. Nazarius also promulgated strange ideas, like the sun and moon as having souls, and the two having sexual relations each month, producing honey and dew. In contrast, Desiderius, the leader of the other Concorezzan party, understood Jesus to be truly human, born of Mary, who ate and was crucified and experienced resurrection. Jesus had the same essence of God but was a lesser being, as was the Holy Spirit, who was subject to the Son. In general, the Desiderian faction moved toward a more positive view of corporeality, an acceptance of the Old Testament, and a greater affinity with contemporary Catholic thought.

After 1250, a series of factors led to the demise of the Concrezzan Cathars, including personality clashes, the inability to attract younger adherents, and the relentless inquisitions.

Комментарии

Пока нет комментариев. Будьте первым!