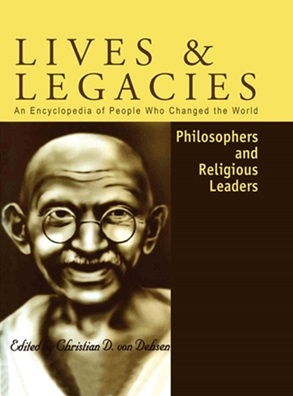

Dehsen - Philosophers and Religious Leaders - модуль BibleQuote

Christian D. von Dehsen - Philosophers and Religious Leaders

Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1999. – 256 p.

ISBN 1-57958-182-X

This volume provides a synopsis of the lives and legacies of 200 men and women from the areas of religion and philosophy who have "changed the world." These individuals have developed, extended, or exemplified ideas fundamental to the way human beings perceive the meaning and purpose of their own lives and of their societies. Some have challenged prevailing convictions and worked for immediate change during their lifetimes; others have proposed new modes of thinking that have flourished only after their passing.

In the following pages we not only summarize the lives of these people, we also explore each person's enduring impact—their legacy. Each has, in some notable way, contributed to the common understanding of fundamental themes of human existence. Some are best remembered as contributors to a specific discipline, all have had a lasting impact on the way people perceive their world. They have shaped the way we understand our reality and provided methodologies for analyzing it.

It was not easy to decide whom to include in our 200. We have tried to span the breadth of history and civilizations to identify 200 men and women from various cultures and perspectives who influenced the shape of our present world. Obviously, we have left out some individuals of note, but we hope the reader will forgive such omissions. By consulting other volumes in this series, the reader can supplement our list and find such personages as Sigmund Freud (Scientists, Mathematicians, and Inventors) and Susan B. Anthony (Government Leaders, Military Rulers, and Political Activists). A final note on locating individuals: given the complexity of transliterating some names into English and the need for alphabetizing those names in a larger list for the book, we have tried to identify individuals from non-Western cultures according to the name most likely used when researching that person in other academic resources. We have also provided common alternative names when applicable. When there were serious discrepancies in transliterations and spelling, we used Merriam-Webster's Biographical Dictionary as our final authority.

* * *

Kant, Immanuel

Leading Enlightenment Philosopher

1724-1804

Life and Work

Immanuel Kant was the foremost thinker of the Enlightenment and one of the most influential philosophers since 1600.

Kant was born into a pious Lutheran family on April 22, 1724, in Konigsberg, Prussia. In 1740, he enrolled in the University of Konigsberg, from which he received his doctorate in 1755. He spent most of his life at that university, where he was named a full professor in 1770.

Kant analyzed the powers and limits of reason while dismissing traditional claims to knowledge about God, immortality, or anything beyond sensory experience. Kant also argued that reason gives a basic moral law to each person. Moral law makes it reasonable to live as if God existed and as if one had an immortal soul that God would judge. Such faith is reasonable because these matters can be neither reasonably proved or refuted. Just as significant, Kant argues that one can have certain knowledge of basic scientific truths about the world—for example, every event has a cause.

Kant bases these claims on a revolution in philosophy so important that it can be compared to Copernicus's influence in astronomy. Copernicus solved certain astronomical problems by breaking with tradition: he asserted that the Earth is simply another planet that moves around the Sun. Similarly, Kant asserts, against philosophical tradition, that, instead of passively receiving its object of knowledge, the knower unconsciously but constructively organizes input from the senses spatially and temporally. That person then fits these perceptions into pre-given categories of the understanding following the mind's own rules. One thus knows a world of appearances constructed from received sensory data organized by the program of human sensibility, understanding, and reason. The world as it is apart from such construction is unknowable because knowledge arises only filtered through these constructs. Alleged realities such as God, the soul, or free will are also unknowable because they yield no sensory data. One may believe in them, however, based on considerations of morality and theoretical completeness.

Kant calls this philosophizing "critical" because it discloses the limits of knowing and "transcendental" because it involves structures of the mind that make experience and knowledge possible. Kant sets out these views in his three most significant but daunting works: The Critique of Pure Reason (1781), The Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and The Critique of Judgment (1790). These writings brought immediate renown and a flock of admiring students to the 60-year-old author and lecturer. However, the publication of his Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone in 1793 led to controversies with the Prussian government. The government accused Kant of replacing traditional beliefs with rational argument and imposed teaching restrictions on the ailing professor.

Finally, after years of degenerative illness, Kant died on February 12, 1804, uttering the simple phrase, "It is good."

Legacy

Kant's philosophy was perhaps the most important of the Enlightenment and became the philosophical "point of departure" for the work of many others.

Ironically, Kant's efforts to defend the objectivity of scientific understanding while making room for objective moral principles, a reasonable faith in God, and immortality inspired two opposing nonKantian philosophical directions emphasizing different aspects of his thought. Thinkers such as Hermann von Helmholtz (1831-1894) and Friedrich Albert Lange (1828-1875), who accepted the critical limiting of science to the world of rationally constructed appearances, pushed to deny even a reasonable faith. They argued that reality is ultimately a physical mechanism completely determined by independent causal relations. Others such as Heinrich Rickert (1863-1936), ever mindful of the limits of knowledge, wanted to reaffirm a knowledge of the world as it is and retain God, immortality, and free will as knowable based on the reality lying behind appearances.

Already in Kant's lifetime, metaphysical idealists like JOHANN GOTTLIEB FICHTE (1762-1814), Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling (1775-1854), ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER (1788-1831), and above all GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH HEGEL (1770-1831) rejected Kant's limits on knowledge. Each in his own way argued that Kant's transcendental self, the unconsciously active spontaneous ego Kant assumed to lie behind the empirical self, is an aspect of an ultimate entity: a nonpersonal, non-corporeal unfolding Spirit, Mind, or Will. Every facet of reality—nature, human history and activity, and the divine—is irreducibly nonphysical, they argue, and a phase of a systematically knowable purposeful development. Because human knowledge, moral activity, and aesthetic appreciation are the most complete phases of this cosmic development, Kant's limits would disappear into an identity-in-difference (i.e., the recognition of one's own essential being in the other) of the knower and the known.

By the 1860s, such metaphysical pretensions to all-encompassing unity gave way to scientists who maintained that this kind of speculation could yield no knowledge. Helmholtz, Lange, and others down into the twentieth century endorsed knowledge only of a world of appearances, a fundamentally physical, deterministic, mechanized world that excluded empty ideas like God and free will. Later, a number of thinkers commonly called Neo-Kantians investigated the conditions for the possibility of cultural realities such as mythology and modified Kant's approach to encompass new psychological insights and post-Einsteinian science. In moral theory, Kant's idea of reason giving itself moral duties remains, with important modification, a viable account of moral obligation.

Kant's works prepared European thinking for such theories as KARL MARX's revolutionary economics, Albert Einstein's relativity, Sigmund Freud's analysis of the unconscious, and FRIEDRICH WILHELM NIETZSCHE's perspectivism. To paraphrase one thinker, one may philosophize for or against Kant but hardly without him.

Magurshak

For Further Reading:

- Gulyga, Arsenii Vladimirovich. Immanuel Kant: His Life and Thought. Boston: Birkhauser, 1987.

- Hoffe, Otfried. Immanuel Kant. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Kitcher, Patricia, ed. Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998.

Комментарии

Пока нет комментариев. Будьте первым!