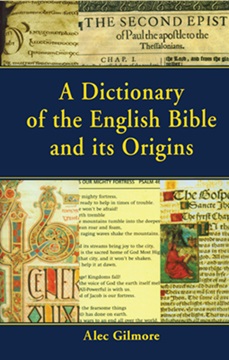

Gilmore - A Dictionary of the English Bible and its Origins - модуль BibleQuote

Alec Gilmore - A Dictionary of the English Bible and its Origins

Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. – Oxon: Routledge, 2013. – 192 p.

ISBN 1-57958-323-7 Fitzroy Dearborn

Why a Dictionary?

Several factors have contributed to this book. One is the good biblical tradition of British nonconformity in which I grew up, with a sound emphasis on the importance of biblical scholarship and a firm rejection of anything approaching bibliolatry or fundamentalism, both of which I associated with people who had either got on the wrong bus or not been sharp enough to alight in time and strike off in a different direction. So it was something of a shock to discover highly intelligent beings preparing themselves for Christian ministry and seeking to explain, let alone defend, many of the issues which for me had never been a problem.

A second factor was a fascination with biblical languages, biblical texts, textual transmission and the growth of the canon which I wanted to share with everybody else. I thought that if only people knew how it all came together they would handle it differently, enrich their understanding and avoid many a heartache. But how? Most people were not going to learn Greek, never mind Hebrew. ‘Text and Canon’ sounded just about the dullest topic you could imagine. Somehow they needed the fruit of scholarship to arouse their interest.

A third factor was the discovery that once the light began to shine many of them did want to know more. Some were the product of very conservative environments from which they longed intellectually to escape. Some were in congregations finding new light and interpretation and wondering whether they could safely believe what they were being told. Some were Bible students who wanted to distract me from what I was trying to say and force me back to first principles.

A fourth factor undoubtedly was a change of climate. In Britain, unlike the USA, from the launching of the Revised Standard Version shortly after the war new translations caught on. J.B. Phillips, William Barclay, Ronald Knox and a few others saw to that. Not with everybody, of course. There was, and still is, a significant rearguard movement, though nowadays, apart from a tiny if vociferous minority, it amounts to little more than a choice between the New International Version, the Revised English Bible and the Good News Bible. So where did all these new translations come from? People began to argue which was the best, which the most reliable, and how they could decide which one to use.

* * *

Caxton, William

(c. 1422–91). Founder of English printing who set up his press in 1476 at the site of the Red Pole in the Almonry at Westminster, on the site of the modern Tothill Street ⋆. His output was huge, including Chaucer and Morte d'Arthur, and he printed some portions of the biblical text in English in his translation of The Golden Legend, but the Constitutions of Oxford ⋆ were still in force and prevented him from printing and distributing the English Bible as a whole.

Great Bible, 1539

Translated by Coverdale ⋆, based on Tyndale's ⋆ translation and the Latin Vulgate ⋆. Owed its origin to Cromwell's ⋆ desire for a revision of Matthew's Bible ⋆ and his request to Coverdale to undertake it. Owed its title to the size of its pages, 16.5 × 11 inches. In the OT it is essentially Matthew's (Rogers ⋆, Tyndale, Coverdale) edition revised, with many of the controversial notes of Matthew dropped. In the NT it is mainly Tyndale, based on the Vulgate.

Changes the order of the books of the NT. Earlier translations had followed Luther in putting Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation at the end in a group by themselves. The Great Bible follows the order of Erasmus ⋆ in his Greek NT, a practice followed by the av ⋆ and other translations after 1539.

Printing began in Paris ⋆ by Grafton and Whitchurch, producers of Matthew's Bible and noted for their devotion and technical skill, but was delayed because the French Inquisitor-General forbade the printers to continue and confiscated their sheets. Representations were made and type, paper and printers were transferred to England, but what had been confiscated was not released, so most of the work had to be done all over again.

An improved edition appeared in 1540, with a preface by Cranmer ⋆ and therefore sometimes referred to as Cranmer's Bible, and containing at the foot of the title page the words, ‘This is the Byble appoynted to the use of the churches’. Five further editions appeared between July 1540 and December 1541. The fourth and sixth editions contain a reference to Cuthbert, Bishop of Durham. This is Cuthbert Tunstall ⋆, formerly Bishop of London, who had resisted Tyndale.

One of the first Bibles to be set up officially in churches, often chained to a pillar or lectern, and the basis for the 1549 Book of Common Prayer. A copy of the first edition, printed on vellum ⋆ in block letters, is in the library of St John's College, Cambridge.

Rabbinic Bibles

The successors to the Polyglots ⋆, sometimes known as ‘extended Bible texts’ because they included commentaries and translations. The first two were printed by Daniel Bomberg ⋆ in Venice, one edited by Felix Pratensis ⋆ (1516–17), the first to divide Samuel, Kings and Chronicles each into two books, and to divide Ezra into Ezra and Nehemiah, and the other by Jacob ben Chayyim (1524–25), the first printed edition to have the Qere ⋆ printed in the margin and which became for a long time the Textus Receptus ⋆ or standard version of the Hebrew Bible ⋆. It also contained several targumim ⋆, including Onkelos ⋆.

Комментарии

Пока нет комментариев. Будьте первым!