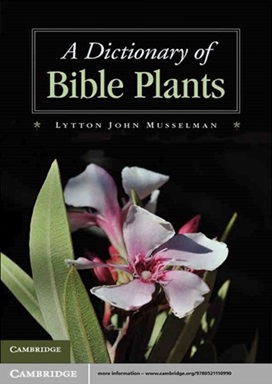

Lytton - A Dictionary of Bible Plants - модуль BibleQuote

Lytton John Musselman - A Dictionary of Bible Plants

New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. – 186 p.

ISBN-13: 978-0521110990

This book describes and illustrates each plant mentioned in the Old and New Testaments and the Apocrypha. It draws on Lytton John Musselman's extensive field investigations from Beirut to Borneo and from the Atlas to the Zagros mountains and includes his own photographs of each plant. The text also reviews recent analytical studies of plants used in materials and technology as well as beer production, medicine, tensile materials, soaps, and other articles. On the basis of these materials, Musselman provides several new plant identifications from controversial biblical passages. In addition, the book surveys the history of biblical plant literature from the time of the Greeks and Romans to the present and reviews and correlates it with biblical plant hermeneutics. To aid readers, extensive references for further study are provided, along with an index to all verses containing references to plants that enables the reader to quickly locate a plant of interest in its textual setting.

* * *

In this book, I review biblical plant literature from the past half millennium. It could be asked if another treatment is needed. Has any new information been obtained? If so, what are the sources of these data? Put another way, what makes this dictionary different from its many worthy predecessors?

First, it is the only dictionary in which each biblical plant is studied in situ. This means not only that each plant was seen and photographed in the field but also that indigenous knowledge about the plant and its uses was gathered. In other words, each entry has a strong ethnological basis, essential to a proper understanding of the plant in its scriptural context, as noted by several earlier writers. Collecting this knowledge involved years of fieldwork from Beirut to Borneo and from the Atlas to the Zagros mountains.

Second, research into the utilization of a crop in ancient eras often revealed the basis of misunderstandings of the texts. One of the best examples of this is the almost exclusive use of emmer wheat in Egypt during biblical times, a crop that required additional specialized preparation not necessary for modern wheats.

Finally, extraordinary advances in analytical processes in archeology, including the development of the science of archeobotany, have elucidated the plants that produced ancient products, for example, the plants used in Egyptian embalming, and have shown the extraordinary ability to determine the composition of materials found in vessels. All this new information is now handily available through immense databases.

The plan of the book is simple: plants are arranged alphabetically by their most frequently used English names, and their scientific names are also provided. For each entry, I do not exhaustively review how the plant has been treated by earlier writers; however, I place emphasis on plants that I consider to be mistreated and note those features necessary to understand the context in which the plant is used in the text. Verses in which the plant is mentioned are listed.

* * *

Cinnamon

Cinnamomum verum

; Also CassiaC. aromaticum

[Hebrew qinnamon; Exodus 30:23; Proverbs 7:17; Song of Solomon 4:14

[Hebrew qiddah; Exodus 30:24; Psalms 45:8; Ezekiel 27:19

[Greek kinamomon; Revelation 18:13

As it is today, cinnamon was a valued commodity in biblical times. The present-day spice known as cinnamon is derived almost exclusively from the bark of the shrub Cinnamomum verum, which is considered to be superior in quality to C. aromaticum, known as cassia. I find it difficult to distinguish between the aroma of the two, although cassia's aroma is less intense. Cassia (not to be confused with the unrelated genus of legumes) and cinnamon bark can be used as a spice as well as for oil, and oil can also be distilled from the leaves of each.

What is the difference between cassia and cinnamon? Miller (1998) suggests that cassia was more widely used in the ancient world because it had long been cultivated in China. True cinnamon, on the other hand, was collected from the wild in the East Indies and was therefore more precious. Both were extensively traded over well-developed trade routes (Schoff, 1917; Miller, 1998). Perhaps the two terms qinnamon and qiddah were applied individually to the product of the leaf or of the stem.

Both cassia and cinnamon are small trees but are grown as shrubs for the bark and leaves. Stems are cut, and the bark is stripped off and dried. Sri Lanka is the world's largest producer of cinnamon.

In addition to being a constituent of the anointing oil (Exodus 30:23), cinnamon was valued as a perfume, as in the harlot's bed in Proverbs 7 and the redolent garden of Song of Solomon 4:14. Likewise, cassia's fragrance is highlighted in Psalms 45:8: "All your robes are fragrant with myrrh and aloes and cassia; from palaces adorned with ivory" (NIV).

As a valued object of trade, cassia is mentioned among the merchandise sent to Tyre (Ezekiel 27:19), as is cinnamon in the traffic of Babylon (Revelation 18:13).

Sweet Cane

Acorus calamus

[Hebrew qaneh; Exodus 30:23; Song of Songs 4:14; Isaiah 43:24; Jeremiah 6:20; Ezekiel 27:19

Sweet cane has long been an important component of incenses and perfumes as well as a widely utilized medicinal plant. It is grown on a large scale in Asia and is readily available in herbal shops as an important component of Ayurvedic medicine. So vital is it to everyday life that many households in Sri Lanka grow it for ready home consumption.

Acorus calamus is very easy to grow, although it thrives best only in wet or damp soil. The thick, tough rhizomes are dug, dried, and used directly or to prepare the oil.

Trade in sweet cane, also known as calamus, has a long and ancient legacy (Schoff, 1917; Miller, 1998). In the Bible, sweet cane is a component of the sacred anointing oil (Exodus 30:23) and had to be imported from distant lands and therefore was of considerable value (Isaiah 43:24; Jeremiah 6:20; Ezekiel 27:19). In these verses, it is no doubt the dried, commercial form of the plant that is intended.

It is therefore a fitting plant to put into an aroma garden along with "henna with nard, nard and saffron, calamus and cinnamon, with all trees of frankincense, myrrh and aloes, with all chief spices" Song of Songs 4:14 (ESV). The attraction of the plant is only in its fragrance as the grasslike leaves and tiny flowers would not draw attention.

Комментарии

Пока нет комментариев. Будьте первым!