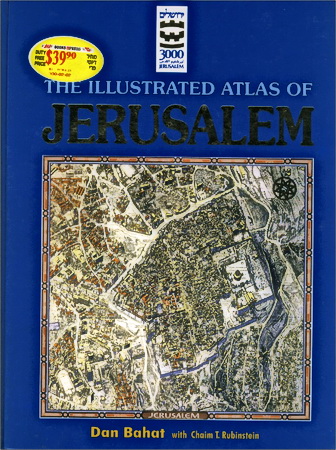

Bahat - The illustrated atlas of Jerusalem

The publication of the first true atlas of Jerusalem is an occasion for much rejoicing, for Jerusalem has held a firm grip on the hearts and imaginations of men and women since King David made it the capital of ancient Israel some 3,000 years ago. Straddling the Judean desert to the east and south, Jerusalem’s mountainous terrain makes the approach to the city difficult for adversaries and tedious for pilgrims. It was the western hill of Jerusalem that the historian Josephus named the City of David. He also called it “the Stronghold,” and in Jesus’ time it became known as the Upper City (Josephus, The Jewish War, 5.4.1). This western spur of the city continues to bear the imprint of David’s memory in David’s Tower at the western (Jaffa) gate of the Old City and in the Islamic Prayer Niche of David close by. What Josephus understood as another hill in the Lower City, farther to the east and referred to as the “hog’s back,” is what we know today from archaeology to be the true City of David.

Such is the charm of the Holy City. What one generation took to be a sacred place another understood to be profane. The area known today as the City of David lies well outside the walls of the present Old City. It was the alleged presence of tombs there that so outraged the sensibilities of religious extremists who sought to halt the City of David excavations. In all these sorts of changes of names and adjustments resulting from new historical interpretations one senses the heavy weight of tradition and faith. Hardly a stone can be moved or a street paved without stumbling upon some important relic of Jerusalem’s past. In the summer of 1989, for example, in laying down a new portion of the street outside Jaffa Gate a section of a medieval street was uncovered and traffic in one of Jerusalem’s busiest intersections was rerouted so that the archaeologists could uncover a few more pages of the history of the city that has been important to so many traditions.

Dan Bahat, Chaim T. Rubinstein - The illustrated atlas of Jerusalem

Jerusalem : Carta, The Israel Map and Publishing Company Ltd., 1996. - 138 pp.

ISBN 965-220-348-3

Dan Bahat, Chaim T. Rubinstein - The illustrated atlas of Jerusalem - Contents

- Picture Sources

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Preface

- The Topography of the City

- The Archaeological Study of Jerusalem

- Ancient History: Until circa 1000 BCE

- The First Temple Period: 1000 BCE-586 BCE

- The Second Temple Period: 538 BCE-70 CE

- Jerusalem at the Time of Jesus

- Aelia Capitolina: 135-326

- The Byzantine Period: 326-638

- The Early Arab Period: 638-1099

- The Crusader Period: 1099-1187

- The Ayyubid Period: 1187-1250

- The Mamluk Period: 1250-1517

- The Ottoman Period: 1517-1917

- Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century: The City Comes to Life, 1830-1917

- The British Mandate: 1917-1948

- Divided Jerusalem: 1948-1967

- United Jerusalem: Since 1967

Bibliography

Index

Dan Bahat, Chaim T. Rubinstein - The illustrated atlas of Jerusalem - The First Temple Period: 1000 BCE-586 BCE

The First Temple period begins with the conquest of Jebus (Jerusalem) by David. The description of this conquest appears in the Bible in two versions: in the Second Book of Samuel (5:6-9) and in the First Book of Chronicles (11:4-7). It would appear that these descriptions are contradictory, since in the first, David is described as actually conquering the city, while Chronicles ascribes the conquest to Joab son of Zeruiah. As the biblical text in the Second Book of Samuel is to a certain extent distorted as a result of various traditions that have merged, it is difficult to determine with any amount of accuracy whether this is a contradictory description or a different account.

The biblical account of the manner in which the city was captured is also enigmatic. At first it was believed that David conquered the city by a ruse: by entering by way of a “gutter” (according to 2 Samuel). According to this version, the city was penetrated by way of the city’s water system, today called Warren’s Shaft, but through recent studies, it became apparent that the shaft was built in a later period, probably at the end of the reign of King Solomon, or of one of the early kings of his dynasty. The Hebrew term tzinor, mentioned twice in the Bible, probably has two meanings: in our case (2 Sam. 5:8), a utensil similar to a pitchfork, used as a magic instrument with which to fend off the enemy and prevent him from conquering the city. This definition is based on the fact that the Jebusite king also used magic and placed the blind and lame on the walls, as a warning that anyone attempting to conquer the city would suffer the same fate. The second meaning of tzinor is a musical instrument. According to this definition, the conquest of the city was carried out in a manner similar to that of the capture of Jericho. Jericho was taken with the aid of shofars and the Jebusite city with trumpets. Support for this theory is to be found in Psalms (42:7) where the term tzinor is also mentioned with what would appear to be a reference to a musical instrument which gives forth a blaring sound. Menachem ben Saruk, a tenth-century Jewish sage, also explained this term as meaning a “musical instrument.”

After the conquest, the city’s name was changed to the City of David. The area of the city remained the same and its boundaries were its ancient walls. The assumption that David expanded the city toward the north, in the direction of the Temple Mount, has not been substantiated. Buildings were added during David’s reign, but were constructed within its original confines. The Bible tells that at first David fortified the city: “And David built round about from Millo and inward” (2 Sam. 5:9) and later also built the king’s palace: “And Hiram ... sent messengers ... and they built David an house” (2 Sam. 5:11). It would seem that the Jebusite fortress, the “stronghold of Zion,” where David took refuge after the conquest of the city, was situated in the northeastern corner of the ancient City of David. This was also the site of David’s palace. An artificial “tell” was discovered here, created by a system of terraces filled with stones, enclosed in box-like shapes placed one above the other. The estimated size of this structure is 39 * 66 feet (12 * 20 meters), but it could have been higher and broader. From the archaeological excavations it transpires that it was David who built these terraces, which acted as additional support for further fillings to solidify and cover over the ancient structure. (So far fifty-five such terraces have been uncovered, but further excavations will certainly uncover more.) It can be assumed that it was upon this tell surrounded by terraces that David built his palace, with the assistance of the builders sent by Hiram, king of Tyre, but the top section of the structure has not remained. Kathleen Kenyon’s excavations revealed architectural remains which could well have been those of an edifice such as a palace. These included such items as a proto-ionic capital similar to that found in neighboring countries dating to the same period. The discovery of this tremendous building project from the time of David enables us to follow the development of the center of government in Jerusalem. At first David built a palace and a center of government on this site—a “house for David” (2 Sam. 5:11)—and once the new center was built by Solomon on the Temple Mount, the old palace began to deteriorate.

Комментарии (2 комментария)

Большое спасибо за ценную книгу!

Спасибо! Полезная для общего знания книга!