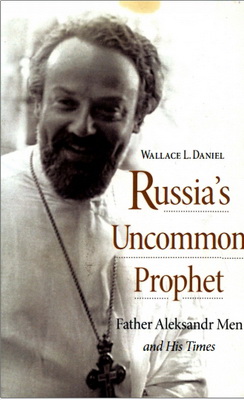

Daniel - Russia’s Uncommon Prophet

During the first half of my academic career, my research and writing focused on Russia in the eighteenth century. This research mainly centered on the social and economic history of the turbulent and colorful period of Empress Catherine the Great, a subject I had always found deeply engaging. But beginning in the mid-1990s, a much different topic became increasingly compelling. Concurrent with the end of the Soviet Union and Russia's attempts to redefine itself, I became interested in its efforts at reconstruction, and particularly in the role of the Orthodox Church in this process. Long suppressed, the victim of nearly seventy years of state opposition, and often viewed as an anachronism and an unnecessary holdover from the past, the Church had suffered one of its greatest assaults in modern European history. After the end of the Communist state, how the Russian Orthodox Church recovered from years of oppression, particularly its efforts to recover its cultural memory and reclaim its heritage, seemed to me to be significant, largely unexplored aspects of its national story. What parts of its historical memory the Church aspired to regain—whether the autocratic, xenophobic elements or those that were nonauthoritarian and outward-looking—would have a large bearing on how the country developed.

Convinced that the subject warranted more attention than it had received in my field, I sought topics that were concrete, revealing practical, day-to-day realities. These endeavors led to a close look at individual parishes, the struggles of certain priests and their parishioners to rebuild, and their efforts to reconceive themselves during the years following the end of the Soviet Union. Whether these attempts either contributed to or undermined the creation of civil society became a primary subject of my research.

From October to November 2005, while in Moscow to participate in two international conferences on religion and society at the Russian Humanities University and the Institute of Sociology of the Academy of Sciences, I began thinking about the possibility of the present topic. I became interested in Fr. Aleksandr Men while researching my book on the Russian Orthodox Church and civil society. Fr. Aleksandr s name and activities came up multiple times among leading proponents of civil society. I was intrigued by his story, and the more I read about him, the greater my interest became.

Returning to Moscow in the summer of 2006 for several weeks to do research in the National Library of Foreign Literature, I met Ekaterina Genieva, the distinguished director of the library and a close friend to Aleksandr Men, and Fr. Georgii Chistiakov, head of the library’s research center on religious literature. Before his untimely death in June 2007, Chistiakov provided me with a great deal of assistance. A kindly, learned, and greatly respected Orthodox priest, Fr. Georgii was a disciple of Aleksandr Men. He allowed me several interviews, which have turned out to be extremely important to my study, particularly his discussion of the theme he considered most significant in Fr. Aleksandrs work: his ecumenical vision. This theme, Chistiakov claimed, was largely unexplored in writings about Fr. Aleksandr.

Chistiakov introduced me to Pavel VolTovich Men, Fr. Aleksandrs younger brother, the director of the Aleksandr Men Foundation in Moscow, and a rich source of information about the late priest. In the last decade, the foundation has published a large number of Mens lectures, papers, and letters, as well as his memoirs, which Pavel Men provided to me before their publication. These materials, inaccessible to previous biographers, contributed a great deal of information about Fr. Aleksandr s personal relationships and primary influences.

Since his death in September 1990, public interest in Aleksandr Men has not diminished, but rather has greatly increased. I have witnessed three events that surprised me with the breadth and depth of the desire to keep his memory alive and to explore the significance of his life and thought. The first took place in New York, in June 2007, at a conference organized by Seraphim Sigrist, then bishop of the Orthodox Church in North America. Devoted to Fr. Aleksandr Mens legacy, the gathering attracted about forty people—scientists, artists, priests, professors, writers, and others—most of them from New York, but also included some who had traveled from Russia and Great Britain to attend. This, it turned out, was an annual event attended by people who met to explore Fr. Aleksandr s teachings and writings.

Wallace L. Daniel - Russia’s Uncommon Prophet - Father Aleksandr Men and His Times

DeKalb: NIU Press, 2016. – 442 p.

ISBN 978-0-87580-733-1 (paper)

ISBN 978-1-60909-194-1 (ebook)

Wallace L. Daniel - Russia’s Uncommon Prophet – Contents

- 1 Murder in the Semkhoz Woods

- 2 Swimming against the Stream

- 3 “The Stalinism That Entered Into All of Us”

- 4 A Different Education

- 5 Aleksandr Men in Siberia: The Formation of a Priest

- 6 First Years as a Parish Priest

- 7 The First Decade: The Writer

- 8 The Transition to Novaia Derevnia

- 9 Fr. Aleksandr and the History of Religion

- 10 Novaia Derevnia: Reaching Out to a Diverse World

- 11 Under Siege

- 12 Religion and Culture (I)

- 13 Religion and Culture (II)

- 14 Freedom and Its Discontents

- 15 “This Was Not a Common Murder”

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Комментарии (1 комментарий)

Большое спасибо!