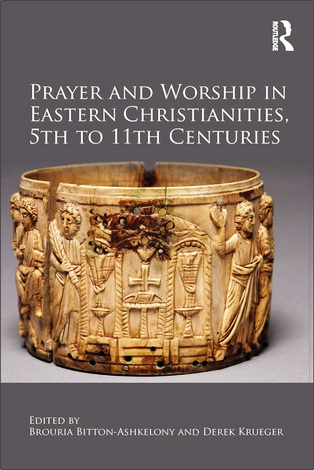

Prayer and Worship in Eastern Christianities

This volume is the fruitful product of a three-day workshop on Prayer and Worship in Eastern Christianities (5th-11th centuries), which took place at the Institute for Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in June 2014. The workshop was part of Brouria Bitton-Ashkelony’s project on Prayer in Late Antiquity, sponsored by The Israel Science Foundation (ISF, grant number 903/11).

We wish to express our deep gratitude to the dedicated staff of the institute for providing us pleasant hospitality during the workshop and, later, for facilitating our labors in preparing this book for publication while we co-directed a research group on the Poetics of Christian Practice at the newly renamed Israel Institute for Advanced Studies. Derek Krueger thanks also the European Institutes for Advanced Studies (EURIAS) Fellowship Programme and the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for funding his research leave.

Brouria Bitton-Ashkelony and Derek Krueger - Prayer and Worship in Eastern Christianities, 5th to 11th centuries

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, London and New York 2017 - 331

ISBN: 978-1-4724-6568-9 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-60197-7 (ebk)

Brouria Bitton-Ashkelony and Derek Krueger - Prayer and Worship in Eastern Christianities, 5th to 11th centuries – Contents

List of figures

List of tables

Notes on contributors

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Introduction: prayer, worship, and ritual practice. BROURIA BITTON-ASHKELONY AND DEREK KRUEGER

- Theories of prayer in late antiquity: doubts and practices from Maximos of Tyre to Isaac of Nineveh. BROURIA BITTON-ASHKELONY

- Prayer and the body according to Isaac of Nineveh. SABINO CHIALA

- Psalms and prayer in Syriac monasticism: clues from Psalter prefaces and their Greek sources. COLUMBA STEWART

- Expressions of prayer in late antique inscriptions in the provinces of Palaestina and Arabia. LEAH DI SEGNI

- Renovation and the early Byzantine church: staging past and prayer. ANN MARIE YASIN

- The power of the eucharist in early medieval Syria: grant for salvation or magical medication? VOLKER MENZE

- The transmission of liturgical joy in Byzantine hymns for Easter. DEREK KRUEGER

- Greek kanons and the Syrian Orthodox liturgy. JACK TANNOUS

- Various orthodoxies: feasts of the Incarnation of Christ in Jerusalem during the first Christian millennium. DANIEL GALADZA

- The therapy for grief and the practice of incubation in early medieval Palestine: the evidence of the Syriac Story of a Woman from Jerusalem. SERGEY MINOV

- Apocalyptic poems in Christian and Jewish liturgy in late antiquity. HILLEL I. NEWMAN

Bibliography

Index of scriptural references

Index

Brouria Bitton-Ashkelony and Derek Krueger - Prayer and Worship in Eastern Christianities, 5th to 11th centuries – Introduction. Prayer, worship, and ritual practice

At the end of antiquity, Christian communities in the Byzantine Empire separated into various polities, depending on whether they accepted or rejected the councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon. These divisions solidified and took on new meanings after the rise of Islam along the eastern and southern edge of the Mediterranean and in Mesopotamia. Church officials within the Byzantium that remained enforced an orthodoxy in flux, a religious system still changing and developing, continuing to debate emerging forms of worship, including collective and individual prayer and the celebration of the eucharist. Beyond Byzantium’s medieval borders in the world of emergent Islam, Christian traditions also continued to develop, drawing on their ancient roots while adapting to their geographic, linguistic, and political environments. Christian division did not simply mean Christian difference. Before and after the rise of Islam, both under the control of the Eastern Roman Empire and in the lands of successive caliphates, groups distinct in their allegiances nevertheless shared a common religious heritage and recognized each other, even in their differences, as kinds of Christianity. By looking at prayer, ritual performance, liturgy, hymnography, and the material culture of worship, rather than focusing on doctrinal differences, we forge a new conversation about the diversity of Christianities in the late antique and medieval eastern Mediterranean, one centered on the history of practice.

While scholars have long explored processes by which these communities became and remained doctrinally distinct, the continuities and similarities in their religious practices merit more attention. Forms of prayer and worship developed in parallel, in part because of common origins, in part because of ongoing transmission across doctrinal, linguistic, and imperial boundaries. Shared ritual patterns maintained common elements even as they continued to be augmented in their various settings. Commitment to common biblical and patristic modes of thought and expression meant competing orthodoxies shared patterns of scriptural reading and interpretation. Even as church leaders worked to differentiate communities, they endorsed common theories of ritual efficacy, styles of the self, and communal expression that they shared with Christians they regarded as heterodox. In the chapters that follow, prayer books, liturgical rites, the material culture of ritual and devotional objects, and the architecture and inscribing of liturgical spaces provide evidence of shared patterns and shared expectation regarding Christian devotion.

The essays collected here shift the focus for the study of varieties of late antique and medieval eastern Christianities from the realm of theology to the realm of practice. This distinction, however, is fluid, productive, and problematic. Our interest in practice incorporates an interest in the development of theory. At the foundation of the modern academic study of religion, Émile Durkheim defined religion as a system of thought and practice. Since the work of Catherine Bell and Talal Asad, however, scholars have come to appreciate that thought is itself a mode of practice, and that all religion consists in practice. Ancient and medieval Christian sources provide both descriptions of religious actions and explanations for why they should be done the way they are done. In that sense theology and theorization are neither separate nor absent from religious practices. Sometimes assumptions about ritual remain implicit, while in other instances rubrics for prayer and worship – and the discourses about them – carry on elaborate theorization, not only instructions for how to conduct Christian ritual life but a native account of why.

Many of the following essays interrogate elements of continuity and change over time as forms of devotion moved from place to place, crossing boundaries of language and polity. The religious changes from late antiquity to the middle ages are perhaps most noticeable in the domain of prayer. In the second and third centuries of the common era, religious professionals and intellectuals, pagan, Jewish, and Christian, expressed grave doubts about the ancient religious systems, the efficacy of sacrifice and prayer, and the forces that govern human life, such as providence and fate. This period saw the decline of institutional sacrifices and the genesis of various substitutes. The very idea of sacrifice could be spiritualized. Greek philosophers developed the notion of “intellectual sacrifice,” while the rabbis conceived the studying and interpreting of biblical rules concerning sacrificial worship in the Temple in Jerusalem – now destroyed – as a form of sacrifice in itself. The slow and steady emergence of public and obligatory prayer in Judaism compensated for the end of Temple. Although late ancient Jewish and Christian thought shared the conception of prayer as a substitute for sacrifice, Jewish discourse eschewed philosophical inclinations, and thus the discussion regarding prayer in late antique Judaism and in Christianity went in different directions. Late antique Judaism never developed a theory of individual prayer, even though instances of prayer do feature in the mystical traditions, such as the Hekhalot literature, as well as in the nonmystical rabbinic tradition. Christians, by contrast, interrogated the mechanisms and functions of prayer, theorizing its centrality in Christian devotion.

Комментарии

Пока нет комментариев. Будьте первым!