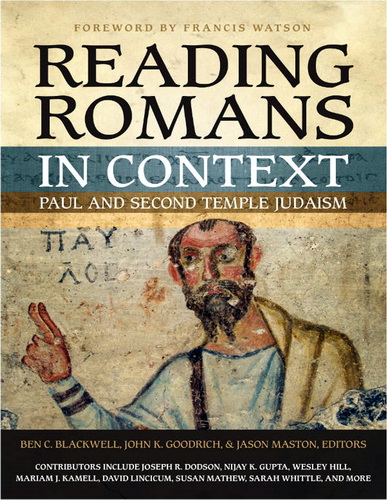

Blackwell, Goodrich, Maston - Reading Romans in context - Paul and Second Temple Judaism

It is easy to suppose that the books that make up the Bible are set apart from all other books and that they relate only to each other. The biblical writings are typically contained within the confines of a single volume, identified as “Holy Bible” and marked out from other books even by its physical appearance: leather covers, perhaps, or gilded page edges or specially fine quality paper or a double-column format. Yet the familiar single-volume Bible is far more characteristic of the second Christian millennium than of the first. In the early church there was no Bible — only “Scriptures” or “writings” occurring individually (as with most of the oldest gospel manuscripts) or in collections such as the Pauline letters. There is little or nothing in the physical appearance of the scriptural books to differentiate them from other books. It is true that early copies of the Christian Scriptures are normally codices (like a modern printed book) rather than scrolls. But the codex was originally the equivalent of a modern notebook or exercise book and had no association with sanctity. During the first Christian centuries, the codex format was increasingly extended to secular books as well.

In one sense, these early Christian scriptural texts were already set apart, in their usage if not in their appearance. They can be referred to as the Holy Scriptures — holy writings — and there was much debate about which texts qualified for canonical status and which did not. Most of their early interpreters move freely between one scriptural writing and another but are less likely to seek connections with texts outside the canonical boundary. Yet users of the Christian Scriptures also read and valued other texts. We know this because so much of the surviving Jewish literature from the Second Temple period was preserved within Christian rather than Jewish communities. Some of the most important of these texts have survived only because they were thought worthy of translation into languages such as Armenian, Church Slavonic, or Ethiopic (Ge‘ez), in the expectation that Christian readers would benefit from reading them alongside the canonical literature.

These texts are highly diverse, catering to all theological tastes and abilities. For the Christian intellectual, the philosophical theology of Philo of Alexandria revealed unsuspected depths beneath the simple surface of Genesis or the rest of the Pentateuch. The writings of Josephus provided a wealth of historical information about the Jewish context of Jesus and the early Christians. Texts attributed to Enoch, Ezra, and Baruch stirred the imagination of the apocalyptically inclined, helping them to view the present world in the light of its unseen but greater heavenly counterpart. A great store of practical advice for Christian living could be found in the Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Ben Sira, commonly called Sirach. The Book of Tobit provided both edification and entertainment. In their different ways, these texts engaged with many, if not all, of the fundamental issues of Christian Scripture. Even though they were not themselves scriptural and their teaching was not regarded as infallible, they were valued for the light they could shed on the canonical texts. No one seems to have worried that the holiness of the Holy Scriptures is compromised when they are read alongside nonscriptural texts that share a concern with the scriptural subject matter.

Ben C. Blackwell, John K. Goodrich, Jason Maston - Reading Romans in context : Paul and Second Temple Judaism

Zondervan, 2015

ISBN 978-0-310-51795-5 (softcover)

Ben C. Blackwell, John K. Goodrich, Jason Maston - Reading Romans in context : Paul and Second Temple Judaism - Contents

Copyright Page

Dedication

Contents

Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Psalms of Solomon and Romans 1:1 – 17: The “Son of God” and the Identity of Jesus

- 2. Wisdom of Solomon and Romans 1:18 – 2:5: God’s Wrath Against All

- 3. Jubilees and Romans 2:6 – 29: Circumcision, Law Observance, and Ethnicity

- 4. 4QMMT and Romans 3:1 – 20: Works of the Law and Justification

- 5. The Epistle of Enoch and Romans 3:21 – 31: The Revelation of God’s Righteousness

- 6. Sirach and Romans 4:1 – 25: The Faith of Abraham

- 7. Community Rule and Romans 5:1 – 11: The Relationship Between Justification and Suffering

- 8. Philo of Alexandria and Romans 5:12 – 21: Adam, Death, and Grace

- 9. Wisdom of Solomon and Romans 6:1 – 23: Slavery to Personified Powers

- 10. Sirach and Romans 7:1 – 25: The Human, the Law, and Sin

- 11. 4 Ezra and Romans 8:1 – 13: The Liberating Power of Christ and the Spirit

- 12. The Greek Life of Adam and Eve and Romans 8:14 – 39: (Re-)Creation and Glory

- 13. Philo of Alexandria and Romans 9:1 – 29: Grace, Mercy, and Reason

- 14. Philo of Alexandria and Romans 9:30 – 10:21: The Commandment and the Quest for the Good Life

- 15. Tobit and Romans 11:1 – 36: Israel’s Salvation and the Fulfillment of God’s Word

- 16. 4 Maccabees and Romans 12:1 – 21: Reason and the Righteous Life

- 17. Josephus and Romans 13:1 – 14: Providence and Imperial Power

- 18. 1 Maccabees and Romans 14:1 – 15:13: Embodying the Hospitable Kingdom Community

- 19. Tobit and Romans 15:14 – 33: Jewish Almsgiving and the Collection

- 20. Synagogue Inscriptions and Romans 16:1 – 27: Women and Christian Ministry

Glossary

Contributors

Passage Index

Subject Index

Author Index

Комментарии

Пока нет комментариев. Будьте первым!