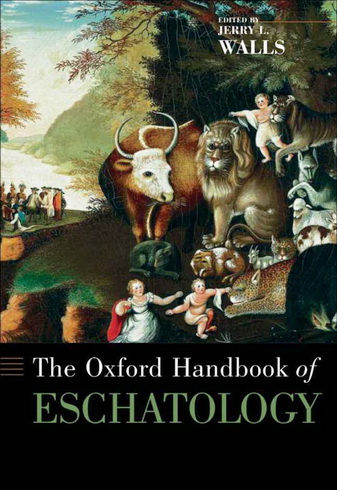

Walls - The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology

I wish to thank several people for invaluable assistance in producing this volume, beginning with the long list of outstanding scholars who signed on to write for it and followed through with the excellent essays below. Much of my own work on the volume was done during a sabbatical granted by Asbury Seminary.

I am grateful to William Abraham and Craig Hill for sage advice and suggestions at the inception of the project. The editors at Oxford University Press were characteristically supportive and helpful in all phases of its production. Thanks in this regard to Cynthia Read, Daniel Gonzalez, Stacey Hamilton, and especially Theo Calderara. Elizabeth Victoria Glass participated in numerous discussions on eschatological topics over the course of preparing this volume and also read and offered insightful comments on my chapter and introduction. Morgan A. Mercer provided perceptive observations on cover art. Sandy Martens was cheerful and proficient in preparing the manuscript for final submission. And, of course, I must mention my children, Angela Rose and Jonathan Levi, who always have a hand in my books if for no other reason than because they bring joy to my life in a way that portends the eschaton.

The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology

Edited by Jerry L. Walls

Oxford University Press, 2008

ISBN 978-0-19-517049-8

Jerry L. Walls - The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology - Contents

Contributors, Introduction, Jerry L. Walls

PART I HISTORICAL ESCHATOLOGY

A. BIBLICAL AND PATRISTIC ESCHATOLOGY

-

1. Old Testament Eschatology and the Rise of Apocalypticism, Bill T. Arnold

-

2. Apocalyptic Eschatology in the Ancient World, John J. Collins

-

3. The Eschatology of the New Testament Church, Christopher Rowland

-

4. Eschatology and the Quest for the Historical Jesus, Benedict T. Viviano

-

5. Eschatology in the Early Church Fathers, Brian Daley

B. ESCHATOLOGY IN WORLD RELIGIONS

-

6. Jewish Eschatology, David Novak

-

7. Muslim Eschatology, William C. Chittick

-

8. Buddhist Eschatology, Jan Nattier

-

9. Hindu Eschatology, David M. Knipe

-

10. The End Is Nigh: Failed Prophecy, Apocalypticism, and the Rationalization of Violence in New Religious Eschatologies, Christopher Partridge

PART II ESCHATOLOGY IN DISTINCT CHRISTIAN TRADITIONS AND THEOLOGICAL MOVEMENTS

-

11. Roman Catholic Theology, Peter C. Phan

-

12. Eastern Orthodox Eschatology, Andrew Louth

-

13. Protestant Theology, Gerhard Sauter

-

14. Fundamentalist Theology, Robert G. Clouse

-

15. Pentecostal and Charismatic Theology, Frank D. Macchia

-

16. Process Eschatology, David Ray Griffin

-

17. Liberation Theology: A Latitudinal Perspective, Vítor Westhelle

-

18. Eschatology in Christian Feminist Theologies, Rosemary Radford Ruether

PART III ISSUES IN ESCHATOLOGY

A. THEOLOGICAL ISSUES

-

19. Church, Ecumenism, and Eschatology, Douglas Farrow

-

20. Millennialism, Timothy P. Weber

-

21. Eschatology and Resurrection, Stephen T. Davis

-

22. Heaven, Jerry L. Walls

-

23. Hell, Jonathan L. Kvanvig

-

24. Purgatory, Paul J. Griffiths

-

25. Universalism, Thomas Talbott

-

26. Annihilationism, Clark H. Pinnock

-

27. Death, Final Judgment, and the Meaning of Life, David Bentley Hart

B. PHILOSOPHICAL AND CULTURAL ISSUES

-

28. Modernity, History, and Eschatology, Wolfhart Pannenberg

-

29. Eschatology and Politics, Stephen H. Webb

-

30. Eschatology and Theodicy, Michael L. Peterson

-

31. Human Nature, Personal Identity, and Eschatology, Charles Taliaferro

-

32. Ethics and Eschatology, Max L. Stackhouse

-

33. Cosmology and Eschatology, Robert Russell

-

34. Eschatology and Epistemology, William J. Abraham

-

35. Time, Eternity, and Eschatology, William Lane Craig

-

36. Near-Death Experiences, Carol Zaleski

-

37. Eschatology in Fine Art, Heidi J. Hornik

-

38. Eschatology in Pop Culture, Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence

-

Conclusion: Emerging Issues in Eschatology in the Twenty-First Century, Richard Bauckham

Index

Jerry L. Walls - The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology - Introduction

“CHRIST has died; Christ is risen; Christ will come again.” These pregnant lines, affirmed by Christians during the celebration of the Eucharist, sum up in pithy fashion the heart of their belief. These lines also bring into vivid focus how thoroughly and profoundly eschatological is the faith that calls Jesus of Nazareth the Christ. Although “Christ” has come to be used as a name, it was originally a title that means “messiah.” Christian faith is thus messianic faith, faith in a savior who has come to deliver us and set up his kingdom. Contrary to Jewish expectations, Christians proclaim that the Messiah has died and that his shameful death is the very means to our salvation and deliverance.

The salvation that Christ achieved is holistic in nature and as such is eschatological in its ultimate dimensions. This point was vividly conveyed in a climactic scene in Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ. In this scene, Christ looks up at Mary and says: “See, Mother, I make all things new.” Most significantly, this line comes not from the Gospels, but from a passage in the Book of Revelation that describes the new Jerusalem coming down from heaven to earth. When this happens, God will dwell with men and be their God in the fullest sense of the word. Death, mourning, and crying will be no more for the old order of things will have passed away when all things are made new. Nothing less than this was implicit in the suffering and death of Christ.

The significance of his death was not understood at the time that it occurred, however. Only after he was raised from the dead did it become clear not only who had died on the cross when Jesus of Nazareth breathed his last breath, but also what it meant for the whole world. In his Pentecost sermon, Peter explained that Jesus had died according to God’s foreknowledge and purpose, but that he had been raised from the dead and exalted to the right hand of God in fulfillment of Psalm 110:1: “The Lord said to my Lord: ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.’” Then he made this startling announcement to his listeners: “God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Christ.” In raising Jesus from the dead, God made him the Christ. Later Christian teaching would interpret this to mean not that Jesus literally became Lord and Christ in his resurrection, but that he was disclosed to be what he had been from all eternity, the eternal Son of God, the second person of the Trinity. As Peter had put it earlier in his sermon, “it was impossible for death to keep its hold on him.” Christ is risen because he is divine. Christ could die because he was also truly and fully human. But having died and risen, he has been revealed as a messiah who has defeated even the last enemy, death itself. And yet death continues unabated, it seems.

That there is more to the story is suggested by the quote from Psalm 110. The key word is “until.” Christ is exalted to the right hand of God, where he is seated “until.” In a sermon shortly after his Pentecost sermon, Peter put it like this: “He must remain in heaven until the time comes for God to restore everything, as he promised long ago through his holy prophets.” The story will reach its proper end when the promises of God are fulfilled in the restoration of everything to the end for which it was created.

Jerry L. Walls - The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology - THE MEANING AND MOTIVATION OF ESCHATOLOGY

The word “eschatology” comes from the Greek word eschatos, which means “last.” Eschatology is thus the study of the final end of things, the ultimate resolution of the entire creation. So considered, eschatology is obviously cosmic in scope, but it is important to add that the field typically distinguishes between issues of personal and cosmic eschatology. Personal eschatology concerns the final state of individual persons and what will become of them at the end of time.

While the main focus of this volume is Christian eschatology, it also has a section devoted to eschatology in world religions. This section is valuable not only for comparative purposes, but also for understanding the internal logic of different religions and how that logic gives distinctive shape to their understandings of eschatology. The broad definition of eschatology just given, for instance, may apply to theistic religions that hold to a doctrine of creation and a linear view of history and that believe that creation will come to a final end. Buddhism, however, would be a major exception even to this broad definition, and to speak of “Buddhist eschatology” requires careful qualification, as the chapter in this book on that subject makes clear.

As the term is primarily used in this volume, however, it is important to understand that eschatology is not only a temporal concept, but a teleological one as well. Things will reach their end when they achieve the purposes for which God created them. A crucial component of Christian teaching about Jesus is that he was a man who did the will of the Father perfectly, and who thus achieved the end for which human beings were created. In this sense, his whole life was eschatological. As the second Adam, he shows us how human beings will live when they are transformed and delivered from the power of sin introduced into the human race by the first Adam. Moreover, his resurrection is an eschatological event because it is the first example of what will happen to all believers at the end of time. As Paul put it: “For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive. But each in his own turn: Christ, the firstfruits; then when he comes, those who belong to him.”

As we survey our world, it is apparent that it is far from the ends for which the God of love created it. Indeed, many are doubtful that there even is a God of perfect power and goodness, let alone a Savior who has defeated death and evil and is reigning over this world from a position of supreme authority. It is this ambiguity that requires a resolution; it is this reality that reminds us that the eucharistic proclamation is profoundly incomplete without its final phrase, “Christ will come again.” Without this claim, the notion that Christ is the risen Lord is an unrealistic sentiment.

The author of the Book of Hebrews put the point rather poignantly. This book begins with some of the most exalted Christological language in the New Testament: “The Son is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things by his powerful word. After he had provided purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty in heaven.” A bit later, the author concedes that commonsense observations do not easily align with this lofty description of Christ’s authority: “In putting everything under him, God left nothing that is not subject to him. Yet at present we do not see everything subject to him.” It is in the present that Christians live and proclaim their faith that Christ has died and is risen. And it is in this present that we do not see everything subject to him. A few chapters later, the author of Hebrews famously defines faith as “being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see.” Faith is thus essentially future directed, and its certainty hinges upon events we do not yet see.

Комментарии (1 комментарий)

Супер новость! Будут в клубе переводы отдельных глав этого фундаментального пособия по эсхатологии!